Syllabot: AI Phonics Buddy

Melody Hammer and Cass Scheirer

Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development

Department of Educational Communication and Technology

Experience Design and Artificial Intelligence

New York University

Syllabot: AI Phonics Buddy

Syllabot AI is social robot thats turns a child's imagination into a personalized phonics game — putting them at the center of their own reading adventure!

Abstract

Syllabot is an AI-powered companion robot that focuses on enhancing the early literacy skills of children (ages 3 to 10) through gamification and embodied storytelling. Traditional reading instruction often ignores personalization, multimodal engagement, and physical interaction, making it difficult for children to immerse themselves in text-only reading. Syllabot increases engagement and enhances the reading experience by using artificial intelligence to personalize the story, allowing children to read the story aloud, and using physical interaction to encourage children to continue reading.

Introduction and Background

Syllabot is an AI-powered, gamified reading companion which is designed to support the early literacy development of young children between the ages of 3 and 10. Young learners (ages 3-10) often struggle with attention, phonics, word recognition, and comprehension, requiring interactive and multimodal reinforcement from an instructive body (Ehri, 2005). Traditional reading instruction lacks personalization and fails to address the diverse needs of early learners, especially those with short attention spans or learning difficulties. Research in cognitive science suggests that multimodal learning technologies — combining visual, auditory, and kinesthetic interactions — may enhance retention and comprehension (Mayer, 2021).

Indeed, interactive multimedia approaches to literacy education, such as games (Franceschini et al., 2015; Gorgen et al., 2020), apps (Chuang et al., 2023), and augmented reality books (Şimşek et al., 2023) have been developed in response. These tools have been shown to enhance the reading experience and improve learning, especially for students with learning disabilities.

However, these tools also have multiple limitations. Many of them feature pre-defined stories and require the use of screens, limiting the meaningfulness of the reading content and the potential for embodied cognition to reinforce the representation of literacy concepts. Further, parents remain skeptical of digital applications as a replacement for traditional books (Kucirkova et al., 2020; Azir et al., 2022). Finally, many of these applications still require or encourage parental involvement, which can be hard on busy parents and parents of slow readers (Mudzielwana, 2014; Melody’s personal experience). Few learning designers have explored how AI-enhanced social robots have the potential to target all of these issues by personalizing, physicalizing, and autonomizing the process of learning to read.

Our team found that there was no reading tool on the market that could combine personalized storytelling, physical engagement, and AI support. Therefore, we designed Syllabot, a social reading robot which combines those functions. Throughout the design process, we explored three research questions:

1. How does physical movement impact the reading experience?

2. How does the design of the robot itself impact the reading experience?

3. How does the personalization of the narrative impact the reading experience?

Our project uses AI-powered personalization, interactive storytelling, and embodied cognition to create more engaging and effective reading experiences. A social robot with a visual interface will work with learners to develop a customized, gamified storytelling experience. Real-time assessment, visual cues, and physical movement will help learners learn the words, improve fluency, and strengthen memory.

System Design

Syllabot was designed to integrate personalized storytelling, multimodal interaction, and embodied learning. It was designed to implement personalized and real-time assessment through artificial intelligence to suit the diverse needs of learners. We used AI to generate stories for different children's reading levels and assessed pronunciation through Azure to help children improve their pronunciation and reading fluency.

Needs Assessment

Primary Research

Our primary user research focused on understanding how parents of kids aged 3-10 use or imagine reading technologies, feel about AI, and perceive the reading challenges and toy usage of their children.

Key Research Questions

How do parents assess their children’s reading challenges?

What learning technologies do parents a) already use and b) lack for reading practice?

What attitudes do parents have about using AI in learning contexts?

What are parents’ perceptions of their children’s toy usage?

Our research process involved a quantitative approach to understand how children engage with reading and interactive toys, as well as to inform the design of an AI reading companion.

Research Method: Survey-based

Target Audience: Parents of children 3-10

Sample Size: Survey with 6 parents (10 children)

Voluntary Participation: Participants were self-selected, meaning they opted to respond based on their interest.

Survey Results

1. How do parents assess their children’s reading challenges?

Insight: Children struggle most with recognizing letters and sounds (phonics) and blending sounds into words.

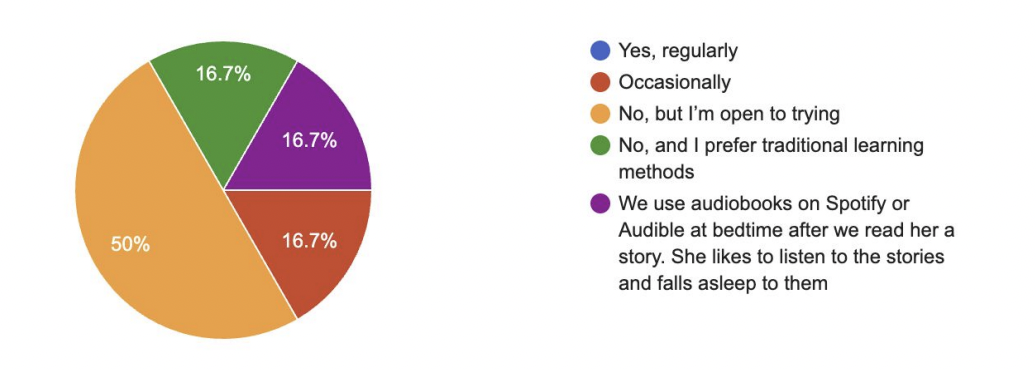

2. Do parents already use learning technologies to help with reading practice?

Insight: The majority of parents do not use reading technologies, and 75% (3/4) of these parents are open to trying.

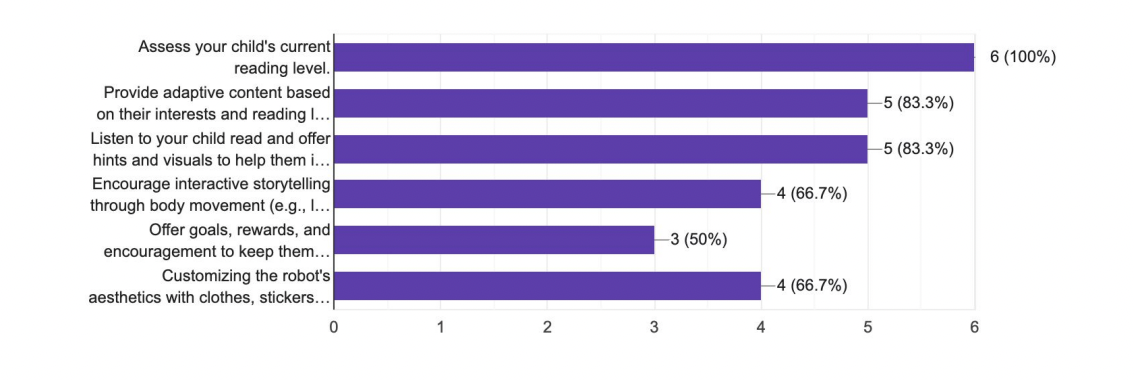

3. What technologies do parents desire to help with reading practice?

Insight: Parents want a solution that can assess their child’s reading level , generate personalized story content, and provide multimodal feedback.

4. What attitudes do parents have about using AI in learning contexts?

Insight: Parents are mainly concerned about privacy and data security when it comes to using AI for learning.

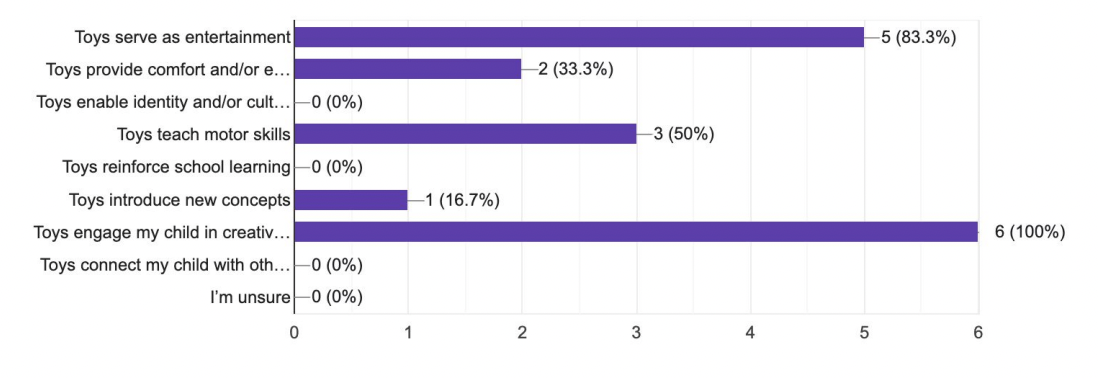

5. What are parents’ perceptions of their children’s toy usage?

Insight: Toys are mainly used to engage children in creativity and entertainment.

Primary Reasearch Needs

Secondary Research

The secondary research focused on surveying existing reading technologies and social robots; and understanding literacy education, how social robots have been used for literacy education, and how the design of social robots can align with children’s aesthetic preferences.

Key Research Questions

What do existing commercial reading technologies and social robots look like?

What are the effects of tech vs. no-tech approaches to literacy education on children and caregivers?

What are the learning outcomes of using social robots for literacy education?

How does the physical design of social robots affect children’s interaction and learning?

Literature Review

Effects of Literacy Education:

1. Young learners can struggle with phonics, attention, word recognition, and comprehension, often requiring adult help (Ehri, 2005)

2. Multimedia literacy applications such as games (Franceschini et al., 2015; Gorgen et al., 2020), apps (Chuang et al., 2023), and augmented reality books (Şimşek et al., 2023) have shown to improve learning and engagement

3. Caregivers remain skeptical of digital applications as a replacement for traditional books (Kucirkova et al., 2020; Azir et al., 2022)

Social Robots for Literacy Education:

1. Social robots can increase child engagement, interest, and excitement during language learning activities (Neumann, 2019)

2. Personalizing the story content of social robots for early literacy education increases engagement, word retainment, and syntax use (Park et. al, 2019)

3. Fully realizing the potential of social robots for early literacy education is limited by a lack of nuanced speech detection models that respect the ungrammaticality and temporality of children’s speech (Kanero et al, 2018)

4. Social robots can improve pronunciation

5. Elementary school children preferred a robotic reading companion to a human 5 one (Yueh et al., 2020)

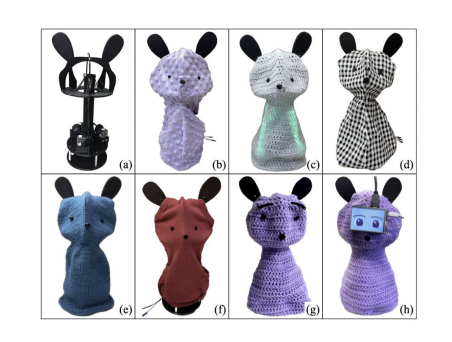

Impact of Robot Body Design:

1. “Build-your-own robot” design strategy increases learner interest in robotics and AI (Shi et al., 2024)

2. Zoomorphic design of robots are the most engaging for children compared with human-like and mechanical designs (Tung, F., 2016)

3. Design features such as edge type, color, and figure have an impact on children’s perception of robot gender and “vibe” (Liberman-Pincu, O. et al., 2021)

Identified Literature Trends

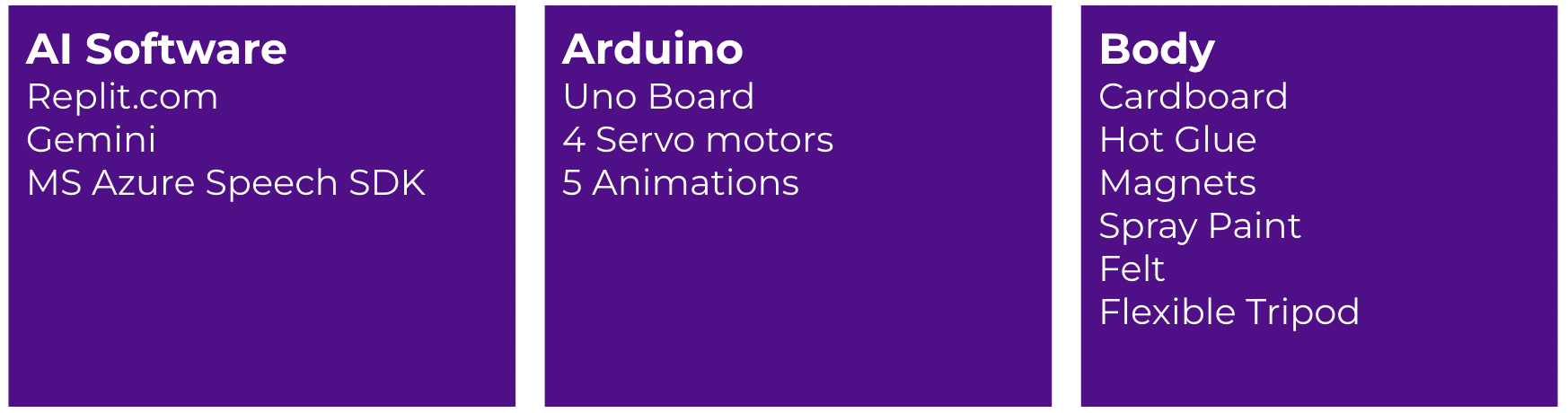

MVP Features and Prototyping Materials

Problem Statement

Young readers (ages 3-10) often struggle with phonics, requiring interactive, multimodal support from adults. Further, traditional reading instruction has limited opportunities for personalization and self-expression , reducing engagement and relevance to educational equity. Caregivers desire a solution in which phonics is creative, independent, and quickly evaluated.

This project introduces an AI-driven robotic reading companion that personalizes each child’s phonics learning process through LLMs, speech recognition, and gamification. By integrating identity-driven stories, pronunciation evaluation, and multimodal feedback, it enhances reading fluency, engagement, and agency , bridging critical gaps in early literacy education — and in caregivers’ teaching bandwidth.

Feature Mapping and MVP Requirements

Link: Design Feature Mapping

Name and Reading Level settings

Selfie of user

Pronunciation evaluation (pass/fail)

Phonetic assessments summary page

Personalized 10-page storybook with child’s name and interests incorporated

Profile creation that saves this information per user

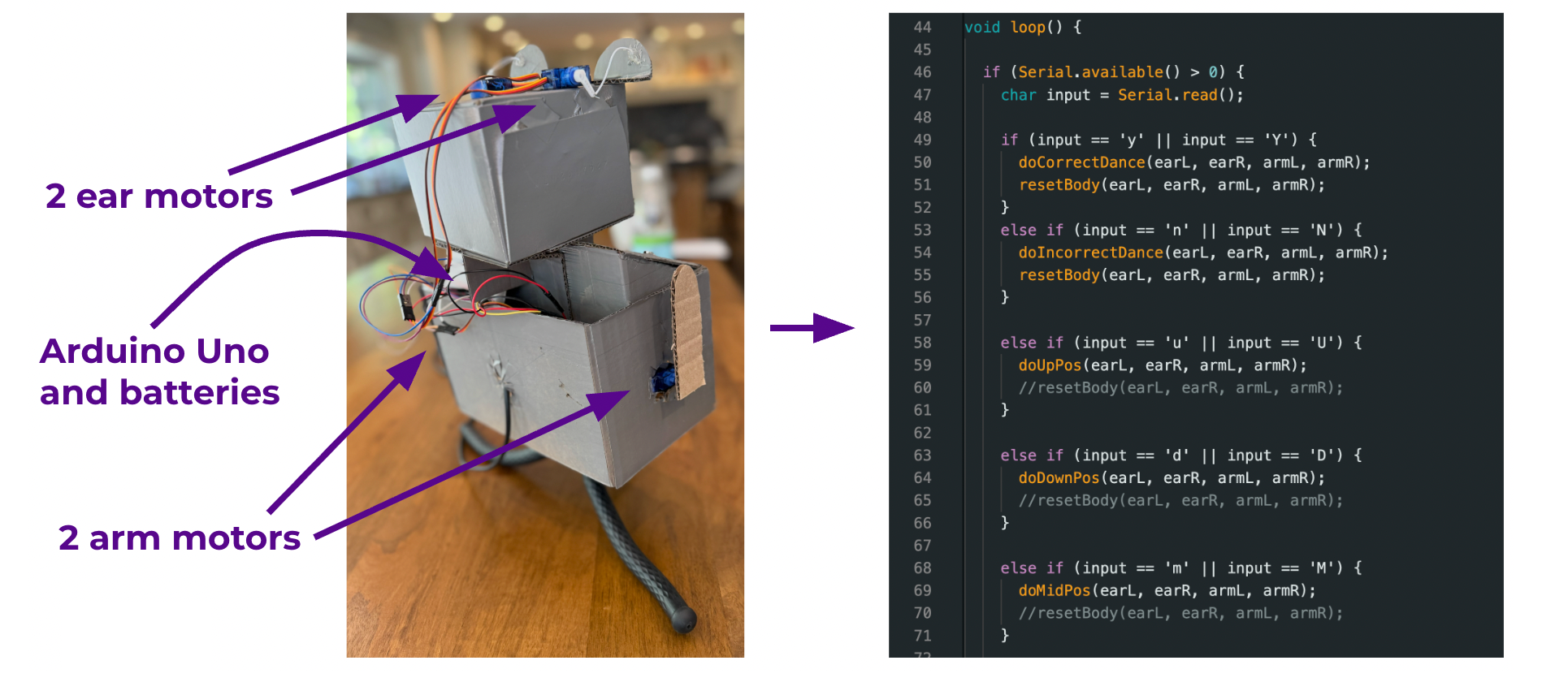

Arduino interactions for ears and arms (WOO)

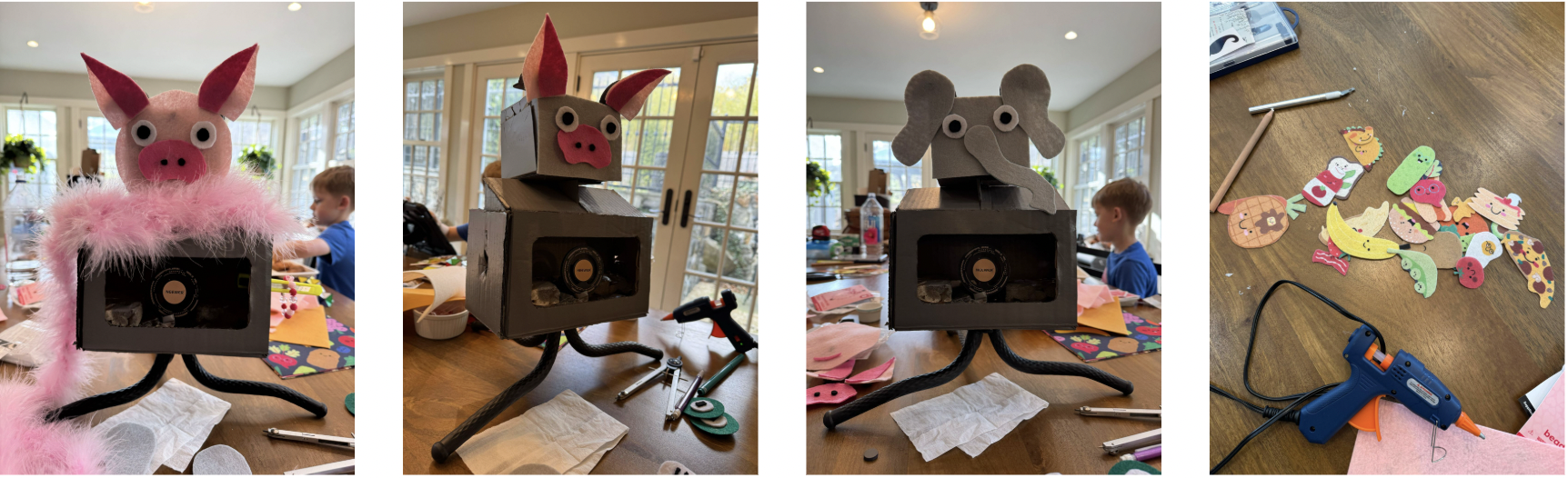

Design your Syllabot body for enhanced user expression

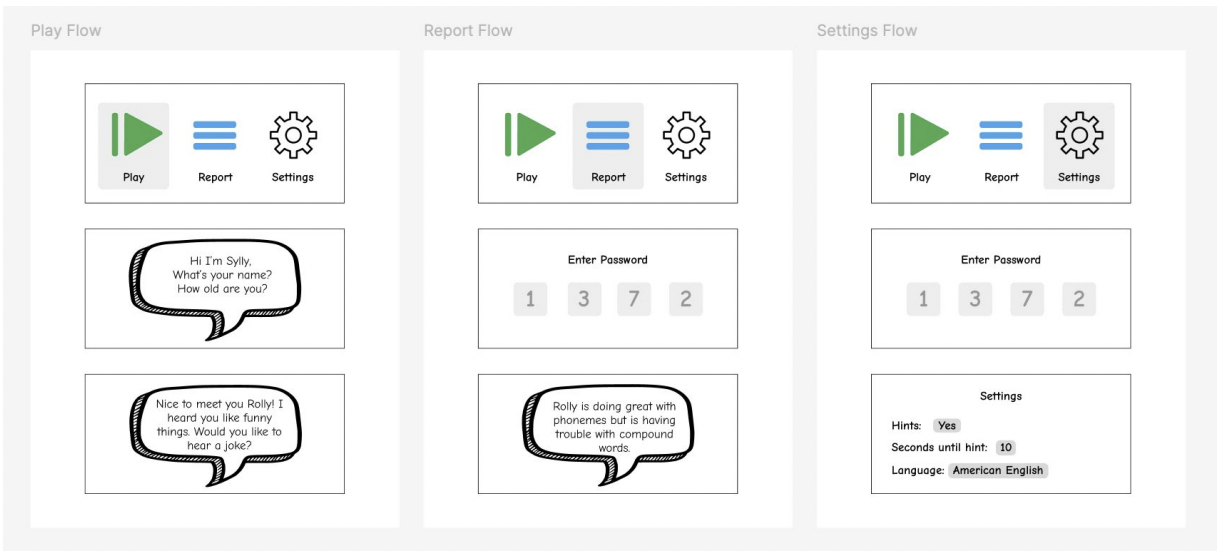

Prototyping Syllabot

Robotic Animations

Syllabot Body Personalization

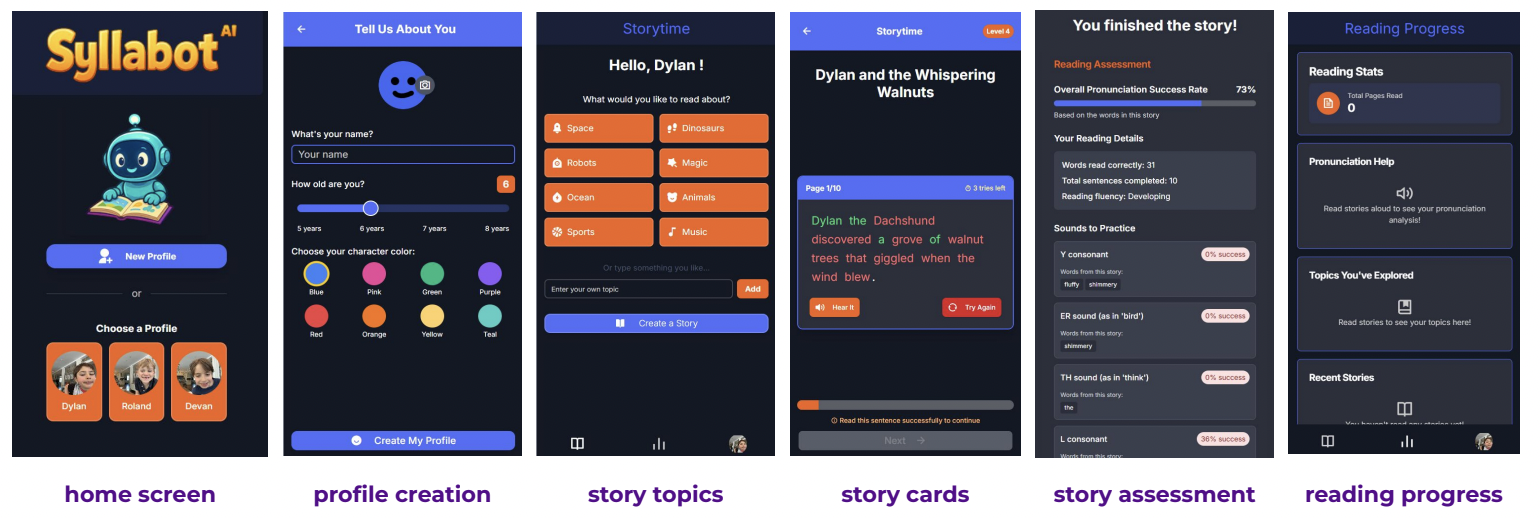

Hi-Fi UX Design and Replit Prototype

Link to Figma Prototype

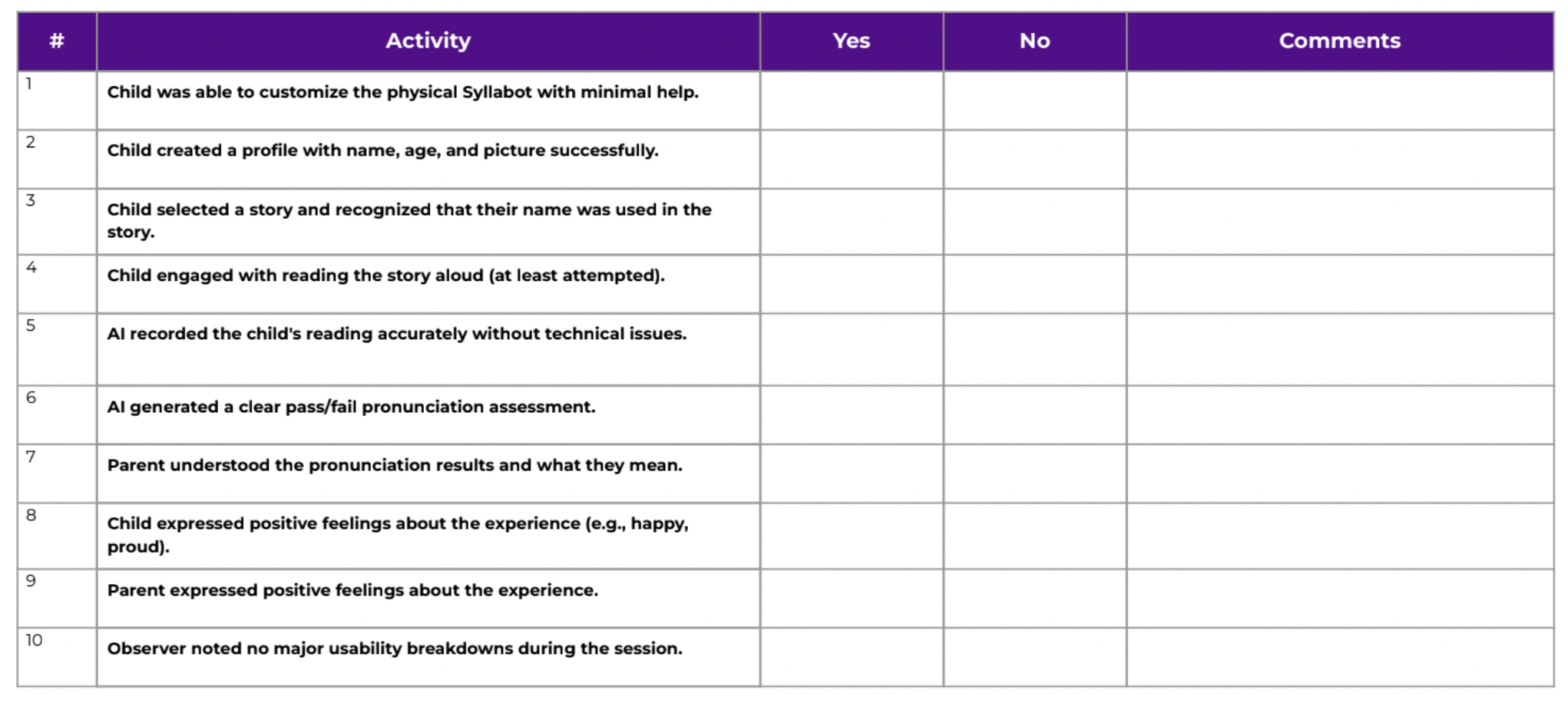

Evaluation Plan

User Testing

Target Audience: Children 6-7 years old

Sample Size: 4 children, 4 parents

Voluntary Participation: Participants were self-selected, meaning they opted to respond based on their interest.

Observational User Testing: Each participant read through a 10-page AI generated story with assistance from parent or observer.

Findings from User Testing

Pronunciation AI Bias

Fairness and inclusivity: Using a pronunciation model trained primarily on adult speech risks unfairly penalizing or misjudging children with speech impediments, second-language backgrounds, or early reading behaviors. This could lead to inaccurate assessments, discouragement, or exclusion of children who do not fit the model’s narrow training profile. Ethically, it’s important to ensure that AI tools used for educational assessment are designed and tested to accommodate diverse speech patterns, abilities, and backgrounds, minimizing bias and avoiding harm to vulnerable learners.

Intuitiveness of Storytime UI

There were issues during story card recording: We discovered that signaling the recording only via text-labelled buttons was not an intuitive interaction for kids. The submit and record buttons would stay the same color — only the text label would change — and these buttons would have to be pressed multiple times in a row at the correct times to properly record and submit a sentence. Kids would press “record” after starting their sentence, press “stop” before they stop speaking the sentence, or even “submit” with no speech having been recorded. Once we updated the design to include more clear visual feedback of the record and submit process, this was less of an issue.

Tangible Interactions & Play

Incorporating play based learning as an icebreaker: The children engaged enthusiastically with the robot, finding enjoyment in both the tangible interactions and the playful feedback. Customizing the robot prior to the reading task served as an effective icebreaker, fostering a sense of ownership and personalization. Additionally, they responded positively to the robot’s animated celebratory movements, particularly when receiving full accuracy on word recognition, reinforcing motivation through playful, embodied feedback.

Personalization & Gamification

Customized stories for each child, followed by an assessment score: The system integrated the child’s name and reading level, using generative AI calibrated by age to deliver a personalized experience.Interestingly, the children largely did not comment on these personalized elements — a finding we view as unsurprising given the ubiquity of personalization in most modern apps. However, the children were highly attuned to the gamified aspects, particularly the progression through levels and the anticipation of reaching a final assessment score after completing ten pages, which sustained their motivation and engagement.

Situativity & Social Discourse

A lasting impression on young learners: After testing Syllabot, the children continued discussing the experience with their peers for days — without any parent or observer prompting. They asked each other what they thought about using the robot, compared how many words they got right, and shared whether they felt the activity was hard or easy. This spontaneous social exchange shows how the experience extended beyond the session itself, embedding into their peer conversations and reinforcing learning through shared reflection.

Ethical Implications

Personalization Bias

While personalizing the reading experience according to learner knowledge, preferences, and needs is one of the main features of Syllabot, there is possibility for this design feature to create stereotype threat. For example, if there is a learner who becomes aware of their learning differences due to the way their progress in the app is presented, this might create anxiety that inadvertently negatively affects their performance and reinforces their differences. It is important that we present feedback at the right time and in positive ways so that this doesn't happen.

Privacy

Our personalization feature also involves collecting and interpreting a large amount of learner data. This data will be kept locally in order to maintain learner profiles on Syllabot, but at any point the parent/guardian can delete this data and/or choose to use default learner profiles to maintain anonymity. In the future, Syllabot will ask the learner during setup if they consent to having their information collected in order to personalize their experience, and will allow the user to define a password on their profile so it cannot be accessed by other users.

Accessibility

Syllabot also incorporates many sensory and input channels into the learning experience: vision, audio, speech, gesture, and touch. The main version of the experience relies on the integration of these channels, but this introduces accessibility issues if the learner cannot interact in these ways (e.g., they are deaf or cannot move their body). Thus there will also be settings to include or remove various input channels in order to make the learning experience more accessible.

Emotional Impact

The customizable anthropomorphic quality of the Syllabot body makes it possible for students to form more intense emotional connections with the device. While we hypothesize this can increase engagement in the learning experience, it can also be considered an ethically questionable design choice because there is potential for issues with the device to be interpreted as harm/pain and cause emotional distress. We combat this by implementing a robotic-sounding voice that Syllabot uses to communicate with the user, hopefully offsetting its other anthropomorphic and emotional qualities.

Conclusion and Next Steps

References

Ali, S., Devasia, N., Park, H. W., & Breazeal, C. (2021). Social robots as creativity eliciting agents. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8, Article 673730. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2021.673730

Azir, I., Zulviana, T., Safitri, D., Harvens, D., & Islamiyah, R. (2022). Parents' Perception of the Use of Digital Book Reading App in Improving English Skills for Early

Childhood. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Science Education in Industrial Revolution 4.0, ICONSEIR 2021, December 21st, 2021, Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.21-12-2021.2317276.

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

Belpaeme, T., Kennedy, J., Ramachandran, A., Scassellati, B., & Tanaka, F. (2018). Social robots for education: A review. Science Robotics, 3(21), eaat5954. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scirobotics.aat5954

Ben Barak, I., & Frost, J. [Idan Ben Barak and Julian Frost]. (2022). Do not lick this book [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DkpKNLTrC0c

Chuang, C., & Jamiat, N. (2023). A systematic review on the effectiveness of children’s interactive reading applications for promoting their emergent literacy in the multimedia context. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2), ep412.

Ehri, L. C. (2005). Learning to read words: Theory, findings, and issues. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(2), 167-188. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

Franceschini, S., Bertoni, S., Ronconi, L. et al. “Shall We Play a Game?”: Improving Reading Through Action Video Games in Developmental Dyslexia. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2, 318–329 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-015-0064-4

Glenberg, A. M. (2011). How embodied cognition contributes to understanding reading comprehension. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(1),1–6.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2011.10.002

Görgen, R., Huemer, S., Schulte-Körne, G., & Moll, K. (2020). Evaluation of a digital game-based reading training for German children with reading disorder.Computers & Education, 150, 103834.

Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign. https://curriculumredesign.org/wp-content/uploads/AI-in-Education-Book-by-CCR.pdf

Hsieh, W. M., Yeh, H. C., & Chen, N. S. (2023). Impact of a robot and tangible object (R&T) integrated learning system on elementary EFL learners’ English pronunciation and willingness to communicate. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-26.

Kanero, J., Geçkin, V., Oranç, C., Mamus, E., Küntay, A. C., & Göksun, T. (2018). Social robots for early language learning: Current evidence and future directions. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 146-151.

Kucirkova, N., & Flewitt, R. (2020). Understanding parents’ conflicting beliefs about children’s digital book reading. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 22, 157 - 181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798420930361.

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108894333

Movellan, J., Tanaka, F., Fortenberry, B., & Aisaka, K. (2009). The RUBI project: A progress report. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1145/1514095.1514101

Mudzielwana, N. P. (2014). The role of parents in developing reading skills of their children in the Foundation Phase. Journal of Social Sciences, 41(2), 253-264.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Neumann, M. M. (2020). Social robots and young children’s early language and literacy learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(2), 157-170.

Park, H. W., Grover, I., Spaulding, S., Gomez, L., & Breazeal, C. (2019, July). A model-free affective reinforcement learning approach to personalization of an autonomous social robot companion for early literacy education. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence (Vol. 33, No. 01, pp. 687-694).

Peura, L., Mutta, M., & Johansson, M. (2023). Playing with Pronunciation: A study on robot-assisted French pronunciation in a learning game. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, (2), 100-115.

Şimşek, B., & Direkçi, B. (2023). The effects of augmented reality storybooks on student's reading comprehension. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(3), 754-772.

Yueh, H. P., Lin, W., Wang, S. C., & Fu, L. C. (2020). Reading with robot and human companions in library literacy activities: A comparison study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(5), 1884-1900.